This story was originally written and published in Ride Magazine's 'Retro Review' in 2010, with crafty editing by Rob Arnold.

The interview took place at the kitchen table of the Neiwands. Gary told many stories from this career and many were omitted as they could easily make up a very colourful book. This interview focuses on the 1993 World Championships in Norway.

* * * * *

The hub used loose steel ball bearings, and alloy dust caps (above). This allowed for the removal of a single bearing and oil instead of grease to decrease friction.

Gary Neiwand's 1993 'Hillman

It was a time when deals were struck between riders to decide titles even at the world championship level… but Gary Neiwand wasn’t prepared to sacrifice his chance for a rainbow jersey, no matter how much his main rival was willing to offer.

Australia had much reason to be proud of the national team that rode at the 1993 track cycling world championships in Hamar, Norway. The pursuit team had won a world title and broken a world record. Shane Kelly was narrowly beaten by Florian Rousseau in the ‘kilo’ for a silver, Danny Day and Stephen Pate claimed silver in the tandem sprint and, notably, Gary Neiwand claimed both sprint and keirin titles – his wait for the successes he deserved was over.

Neiwand is a name that’s synonomous with track cycling in Australia. Gary grew up around bikes and races from as early as he can remember.

The sport coursed through his veins partly due to the DNA passed down to him by parents Ron and Barbara, Ron being an accomplished amateur cyclist himself.

Although Gary excelled at traditional sports, football and cricket, when he was growing up, it was on the bike – and particularly the track – that he discovered his true talents.

Road racing, as Gary would say, is for “failed track cyclists”, adding his friend Stuart O’Grady to that list, even if the 2007 Paris-Roubaix winner was able to win Olympic gold – from the madison, a track event – to his long list of accomplishments. The pair were young winners in Hamar.

While Gary seemed to have been on the scene for years, after making his Olympic debut in Barcelona – finishing second to Germany’s Jens Fiedler in the sprint of the final amateur Games – he was still 22 when he raced to double gold in Norway. A little over a week later, he celebrated his 23rd birthday. (O’Grady, as part of the team pursuit squad, had just turned 20.)

The 1993 sprint podium… Michael Hübner was so upset that he was beaten in the final of the sprint that he refused to attend the podium ceremony. Gary Neiwand and Eyk Pokorny (above) pose with their gold and bronze medals in Hamar.

Although there is humour in Neiwand’s expression when he relates his view on various cycling disciplines, it compounds the single-minded devotion for the short intense battles the banked boards offered. Gifted with more fast-twitch muscle than a hare, Gary’s explosive leg speed, combined with his tactical nouse, was a formidable combination.

Gary Neiwand may have possesed physiological advantages for sprinting, but his commitment to training and the art of sprinting is what ensured the longevity of his career and consistently high ranking.

His 178cm tall stature gave him a low position on the bike, aiding his aerodynamic profile, while his leg speed was unmatched – he still holds the record for greatest ergo speed (with no chain) at the AIS, an unbelievable 300rpm.

Explosive power is important across all sporting disciplines and at the AIS he held the vertical leap record, which Darryn Hill his training partner still concedes is impressive. This final test was one of the favourites of former national coach, Charlie Walsh, the man responsible for guiding the Australian team to success in Hamar and onward until he retired from the position just after the Sydney Olympics.

“I got nothing from it,” said Neiwand about the leap test.

“It’s a good indication but what you do jumping up against a wall means nothing. You don’t get to the start line and look at your opposition and say, ‘Well, how high can you jump?’

Neiwand used MKS pedals. Sprint double straps were cut into two singles to secure cleats on wooden-sole shoes.

“Team pursuiters barely got their toes off the ground but it was meant to be a gauge of the strength of fast-twitch muscles, someone like me who could get quite high. They say white men can’t jump but this is wrong according to that test.”

There is a strong history with Australian cycling and track sprinting. Bob Spears from Dubbo was the first Aussie to win the pro world championship back in 1920. Fifty years later, Gordon Johnson took the title in Leicester, and in 1975 and 1976, John Nicholson won the sprint crown before the start of Koichi Nakano’s 10-year victorious reign.

Stephen Pate claimed two titles, the first in 1988 in Gent when the runner-up, Claudio Golinelli, was later disqualified for doping. The second success for Pate was in 1990 when he and compatriot Carey Hall took gold and silver in Stuttgart… only for both to be stripped of their medals because of drugs.

And then, in 1993, the distinction between professional and amateur cyclists ended: there were now ‘elite’ sprinters.

After the successful reign of Queenslander Kenrick Tucker, Neiwand took over the mantle of Australia’s finest sprinter. It inspired a new generation and his victories in 1993 were a key to unlocking the talents of riders who followed in his tracks, including future world champions from sprint events Hill, Sean Eadie, Ryan Bayley and the late Jobie Dajka.

Almost all AIS equipment from this time was tattooed crudely ‘AIS’ with a dremel. Chainrings and cogs were colour coded for easy calculation of gear ratio.

By 1993, the memory of Pate and Hall’s indiscretions was over and Neiwand was proving to be the prodigy that Walsh (and other key supporters including Peter Bartels) expected he would be. He and Hill headed that generation of sprinters. The two trained competitively in the gym and though Hill was 20kg heavier, he was no more powerful than Neiwand who weighed in at just over 80kg at his prime.

Gary could judge his progress on the track based on his maximum squat ability.

Be it mind games, singing songs, or just joking around and bluffing, Neiwand had the upper hand over his rivals before he even turned a pedal in terms of mental toughness.

His bike handing was so skilful that he would ride in the tram tracks on the way back from the velodrome, then hop deftly out. Prior to an event he would walk around the velodrome to ‘read’ each track, determining the fastest lines through all the bends. This trait he learned from velodrome architect Ron Webb.

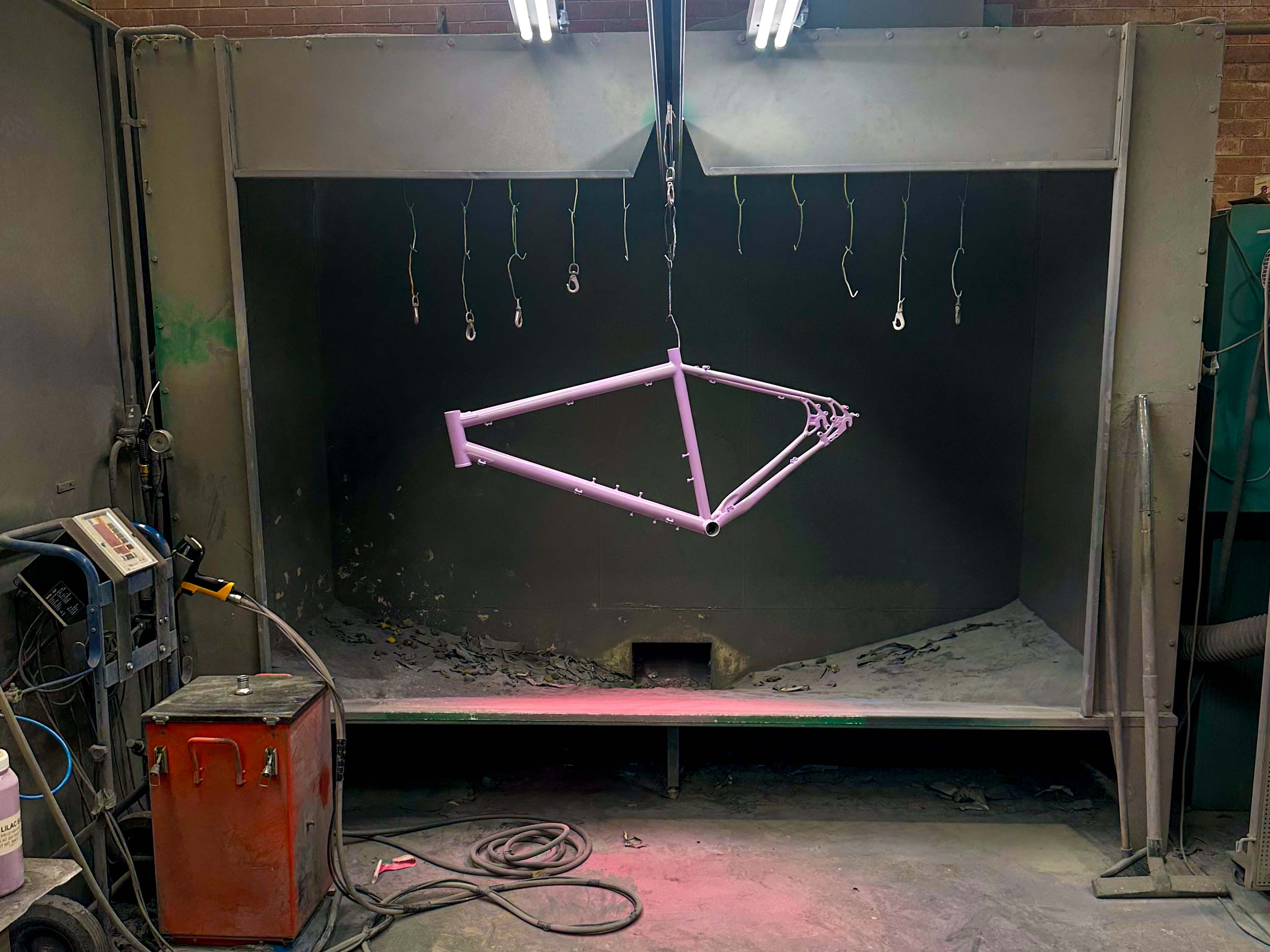

The bike Neiwand used in Hamar in 1993, on a track that would be demolished after the championships, was made in Australia by Bryan Hayes. He built the Columbus Max fillet-brazed frame in 1992 in time for the Barcelona Olympics, drawing inspiration from the famous Cinelli Laser.

Hayes filled the region around the tube junctions and gave shape to the aerodynamic profile of the frame.

Added bulk around the bottom bracket is common on carbon-fibre frames these days but Bryan Hayes added rigidity to Neiwand’s bike with extra steel between the chainstays.

Neiwand was not obsessive about what he was riding, with regard to bike set-up and componentry. With the massive improvements in material technology and sports science it is amazing to believe that Neiwand rode a 9.8 flying 200m on this steel frame with spoked wheels. He favoured smaller gears that he could turn more furiously – a 48x14 combination, for a 92.6-inch gear, was what he rode most consistently.

Though he was never one to get excited by new bikes, when the frame arrived in a box to his home in Elwood, originally a dazzling green and gold, he described it as “pure porn”.

Neiwand had the frame resprayed in the Panasonic Team scheme “because I liked it” prior to the worlds by his sponsor at the time, Hillman Cycles.

The bike came with Campagnolo Record components, and Gary’s preferred Rolls saddle was removed for the new product on the market, the Squadra.

A rear Campagnolo Ghibli disc wheel and front Shamal and Vittoria tyres helped him get around the track in Norway but the bike has been photographed using Shamal wheels that are owned by another star of the school of 1993, Shane Kelly.

The rest of the build is composed of 165mm Campagnolo Pista cranks, DID chain and Shimano Dura-Ace track cogs.

The Duegi wooden-sole track shoes that Neiwand used for his entire career had a basic cleat which wedged onto the pedal plate, secured with a single leather strap on each side that Gary had made by cutting down a pair of double straps, as he found the double strap unecessary and uncomfortable.

At the time, clipless pedals were available, though they were not preferable for the demands of sprinters.

* * * * *

As a kid from Australia, there was little exposure to the international track scene and what possibilities may lie ahead. In 1986, Neiwand moved to Adelaide to train with the South Australian Sports Institute (SASI) under Walsh, prior to the formation of the AIS cycling facility.

Campagnolo C Record Pista cranks (above) were released in 1984. The first generation featured an engraved logo similar to that found on Super Record.

Though the needs of track sprinters differed significantly to road endurance riders who, at the time, doubled up by also forming a decent proportion of the national road team, Walsh managed both and Neiwand was his program’s guinea pig.

Shortly after racing his first world championship, Neiwand moved to Germany to live with his new training partner – the 1990 and 1992 sprint world champion, Michael Hübner.

The German was a mountain of a man, standing 193cm tall and weighing over 100kg. Bulging biceps and massive thighs, he cast an intimidating shadow over the track world. It was from early competitions that Neiwand was inspired by another East German, Lutz Hesslich, who he describes as “the most complete sprinter of all time”.

Living abroad, the young Australian sprinter was paying for not only board.

The East Germans were leaders in the development of sport science at the time and were selling training programs to the likes of Neiwand. Over time it became apparent how much of the program they were divulging, and how much they were keeping to themselves.

As the saying goes, ‘Keep your friends close, and your enemies closer’.

The Germans had good reason to keep Neiwand close. Neiwand and Hübner became good friends on and off the bike, but that all changed in 1993.

Cinelli’s forged alloy stems were not as stiff and reliable as the steel option. A 38cm- wide Nitto NJS B123 steel handlebar (above) and vinyl bar tape complete the cockpit.

The Germans had good reason to keep Neiwand close. Neiwand and Hübner became good friends on and off the bike, but that all changed in 1993.

An amateur competing at the elite championship for the first time in his career qualified fastest with a time of 10.258 for the flying 200m. Jens Fiedler was second with 10.348, Hill third in 10.433, Curtis Harnett of Canada fourth in 10.440, and Hübner fifth in 10.468. Neiwand advanced to the final by beating Federico Paris and Fabrice Colas in the early rounds, then Eyk Pokorny in the semi. Hübner eliminated Marty Nothstein and the training partners would meet in the final.

Hübner approached Neiwand in the infield and offered him 20,000 Deutschmark for the win.

“This was pretty much one-to-one with our dollar at the time,” said Neiwand of the proposal from the soon-to-be-retired veteran.

Neiwand was familiar with buying and selling races at club level, but this was a world championship. He had never won a title and to consider buying or selling one was a shocking proposition.

In a colourful manner, he declined Hübner and became infuriated by the offer. His mind went into overdrive.

In the first round Neiwand was a “mental milkshake”, as he describes it.

The pedals were turning, but his mind was turning faster: “Have I made the wrong decision? How many championships has Hübner bought? Can I beat him?” On a track where all the wins had been from the front he gave Hübner too great a distance into the final lap and lost badly.

Neiwand rode 165mm cranks on a 48x14 gear. At top speed of around 73km/h, on a 92.6-inch gear, this equates to an amazing cadence of 165rpm.

He was shaken and relayed the news to the Australian camp. Bartels, a former sprinter who carved himself a niche in the business world after his cycling career, gave the young pro the ear bashing and confidence boost he needed. Neiwand led from the front and, knowing he was the fastest on the track, put his mind into the muscle and levelled the score.

For the final race, Gary Sutton and Bartels told Neiwand he must get in front as soon as he could.

At the time, under the UCI rules, the lead rider had to remain in front for the entire first lap and, only then, could they track stand and jockey for position. The advisors agreed he could not win from behind. No one could.

Neiwand turned this attitude into motivation and Hübner’s eagerness to lead out made for a complete tactical victory. Billowing with confidence, Neiwand followed his slipstream by a whisker and timed his attack precisely.

When he came around in the back straight Hübner had no answer. Gary Neiwand was world champion.

Neiwand celebrated so long into the night that he arrived the following day not having slept at all. A ghostly pale figure retching over a bin is what Curt Harnett discovered during warm-up.

“You riding the keirin?”

Neiwand nodded.

“Big night?”

Another nod.

With no warm-up, he advanced through his heat using cunning and the least amount of effort possible, then dashed back to the hotel to down a massive steak, chips and fluids before the afternoon’s session.

Columbus MAX tubing was released in the late 1980s. Though only 100g heavier than EL, the cast lugs added 350g so a fillet-brazed construction was favoured by Hayes to take advantage of the stiffer tubeset. Some sections were built up with filler and sanded down prior to painting.

Hübner crashed in his heat, almost falling over himself, though the judges declared another rider responsible. With pride and body both beaten, the German watched from the stands as his former friend lined up for the keirin. “In the final I felt amazing, effortlessly twiddling the pedals.” Through turn three Neiwand noticed Magne duck inside the sprinters line and he was sure he would be disqualified. Knowing he had the leading two riders covered, a final burst of pace in the final stretch secured the double.

Curve Cycling Belgie Spirit | Mercedes Benz AMG

Endless Summer Ride | The Radavist