A BUMP IN THE ROAD OF LIFE.

This is the full ‘directors cut’ of how I broke my neck.

I wrote the story on one of the earlier iterations of this corner of the web. That story and many others got lost in transit but the story in no less vivid in my mind.

The day it happened was Thursday 13 September, 2007.

I’d been married a year, and was working as bike courier come wedding photographer, t-shirt maker, buyer and seller of vintage track frames and parts, all round general hustler.

My interest in bike couriering in Melbourne again was waning after working around the world. I was racing track twice a week, Northern Combines on the weekend, and was even winning in A grade. To cut a long boring story short, I was as fit and strong as I’d even been and just getting going. I had just started ‘training’ under the eye of cycling legend, Jim Pritchard. This chapter of training with Jim, hearing his stories including witnessing Russell Mockridge’s death, the glory days of track racing in Australia, to a young Matt Keenan commenting on his training partners on the rollers is a post in itself. I wish I wrote it all down.

It was a Thursday that September – as track racing at Northcote was that evening. September in Melbourne is spring and it’s a volatile change in the seasons. Gusty winds is the norm and I had a head wind as I pedalled north to Humevale for a few laps up the hill before track that night.

Just before Whittlesea I passed a pair of dead rosella’s by the roadside. It seemed bittersweet to find the birds that are never apart, now eternally together. The rest of the ride was the stock standard push up the hill, and I was sitting comfortably on 28kph all the way. For those that now the 7km climb you’ll be familiar with the sharper bend at the 6km mark with is the only relative increase in gradient the whole climb. I’d been seated to this point and got out of the saddle for this rise. That was the last pedal stroke I made.

//////

It was another session in the ‘pain room’ as Jim called it. I’d ride the rollers, warm up and then he’d tell me what gear to push, for how long, as he sipped his tea in between glances at the stop watch. I hated this. Not so much the pedalling as the not knowing how to measure my effort.

He’d call ‘STOP’ and then give me a break and then back on again. Jim would tell me the benefit of the drill and how it would improve aspects of my riding relative to terrain.

This particular night he brought up the fact of a new team being created for a few of his current riders, and they’d made it known they didn’t want him training anyone outside of the team. He said I had the majority of the tools needed anyway, and Jim didn’t seem to be one to rock any boats. I thanked him for all he’d done to date – but I was also mad which as it turned out was a very handy training tool.

On my way out he mentioned that my front wheel looked a little loose. I didn’t pay it much attention, and rode home.

///////

With this little incline in sight, I stood up and pulled on the bars slightly, the fork tips lifted off the axles. The wheel moved under the bike and as the fork tips returned down they missed the axle, allowing the tyre to grip on the fork crown. This catapulted me head first into the ground.

It felt like my brain rattled inside my skull. I lay flat on my back looking up at the blue sky and my immediate thought was my toes. Can I move my toes?

They moved. Phew! My neck isn’t broken. Still on the ground I reached into my pocket for my phone. The screen showed 10.41 AM – NO SERVICE. Great.

I pondered my predicament for sometime. Knowing there is next to no traffic on the Humevale road, I knew the only way I was getting home involved walking to the main road, a kilometer or so away. That was a long hobble. My helmet was cracked in more places that I cared to count. My saddle and the section of seatpost attached to it lay metres away from the bike. My neck was so stiff I could not move it – but to my own savage stupidity I was trying my best, with both hands. Nothing.

I made it to the road and it wasn’t long before a foursome of cyclists rolled by – one of them I knew from a few races, Tom McDonough. They asked if I wanted to an ambulance. I declined but asked if they could call my Dad at the bottom of the mount and let him know what had happened. No need to make a mountain of this mole hill. I waved them goodbye and sat down gingerly. As the sweet cooled, so did the weather and I shivered in the ditch waiting, trying to move my neck in any direction as I did.

Nearly an hour later, Dad & Mum who are much like Rosella’s, came to my aid. I piled the bike in, with it’s snapped seat pillar and got in the car. A conversation ensued, which turned into a bickering of which hospital I should go to.

Going to hospital would have been the prudent thing, but I could do without the drama and I told them I’d be fine. Nothing a bath couldn’t fix. It was in the bath I called Melodie and told her of my ordeal. I asked if she thought I should go to the doctor and she said yes – so I did.

Mum took me to the Mill Park doctors clinic where I waited to be seen. The doctor suggested I go to Bundoora Radiology for an X-Ray, but was fresh out of neck braces to stabilise my neck.

Another short distance, more waiting and I was X-Ray’d and awaited the results. In the waiting room I called Gonz. I had planned on seeing him at the original Gonz Lab but I didn’t see myself going anywhere soon. My results came through and the radiologist told me I had a broken neck and suggested I go to the Austin Hospital for ‘observation’. This seemed a little weird. Broken necks were supposed to be serious, and the casual delivery of ‘observation’ was at the other end my serious spectrum. It was now mid afternoon and Mum hates driving at the best of times, so called Dad to take me to the Austin.

I remember sitting in emergency, staring at my shoes in the only comfortable position I knew at this point and hearing the familiar click of heels on tiles. Melodie had left work to see me and I could tell she was nearly as shaken. Finally my name was called and I went to the window. I handed my X-Ray across the counter and the nurse pulled them out and dropped them almost instantly.

‘Don’t fucking move’. She said.

‘Is this serious?’ I repled.

‘Deadly fucking serious.’ she said and had now called staff to help secure me to a board with my head strapped to it. I remember hearing her say to a colleague ‘YES – he fucking walked in here like that!’ as my vision was now fixed at the ceiling.

The next few hours was a blur of scans, more X-Rays, CT and MRI to asses the extent. The original X-Rays showed a broken C5 and C6 Spinus Process (that knobby bit you can feel on the back on the veterbrae) but it couldn’t illustrate the fracture of the C1 vertebrae due to the nature and angle of the X-Ray.

Later that evening I had a surgeon above me. My vision was still fixed at an awkward angle. ‘Just got out of surgery. A young guy had a similiar accident to you – except he is never going to walk again’. The weight of that was very heavy. ‘We are going to place you in a halo which is a brace to stabilise your neck. Four titaniums screws are drilled into the third layer of bone in your skull to secure it. You will wear it for three months. You will be fine.’

What I pictured to be a long 3 months on disability flew by. I would have worn it for 3 years if need be.

There are some side stories in there, like me dislodging the halo and having to repeat the process, sleeping wasn’t easy but not as difficult as they told me it would be. Every 2 weeks I would travel to hospital for a shower and change the sheepskin liner.

During the time I had a lot of support from friends, family, and fyxomatosis followers, but none more so than my wife who lived the nightmare with me. The time in the halo gave me a lot of time to think. About life, about the ‘what if I wasn’t so lucky’, a lot of things I’d put on the backburner while I was fixated on racing bikes. A very important lesson I learned is that I am not bullet proof. Not even shotgun pellet proof. I’d spent the past decade dodging cars that travelled like bullets in the world’s busiest cities, done my fair share of dumb things on the road, calculated moves but all with their share of risk and consequence – all come undone on the quietest country road because I failed to check my equipment – truth be told I shouldn’t have bought the used wheels which had the incorrect bearings in order to save a buck. Life is too short to ride shit bikes.

The time flew by and the day before my 30th birthday I had the halo removed. The first question Melodie posed to the doctor was ‘how long does he have to wait before he can ride again?’.

A week later I took my first ride, to Whittlesea and back. It was a slow roll, and performing a head check was slow and difficult but quickly, and with minimal rehab everything went back ‘to normal’. I wouldn’t say everything is back to normal. I rarely race or train, I ride for fun. I take ‘fewer’ risks but once a bike courier, always a bike courier. I continue to wear a helmet, but not always if it’s just to the shops. The helmet saved my life, and most certainly from head trauma and brain damage. Anyone with a physics background could calculate the force applied to my head. 28kph, a distance of 180cm and a dash of gravity acceleration added to that speed, slammed to a halt by the road. Relatively slow when I think of the speeds reached on the same descent. Technology has come leaps and bounds since that day, and because much of the riding I do is on my own I invested in one of these.

I am also continually grateful for the simple gift of good health.

//////

FYXO wouldn’t be what it is if it wasn’t for this chapter in my life. For that I wouldn’t change a thing.

My only advice to you is if you come off your bike, and we all do at some point – don’t hesitate to call an ambulance and definitely see a doctor if you impact your head or back. If you can immobilise yourself until that point – do it. The consequence of not doing so far outweigh the price of being cautious and diligent. I’ve lost count of the stories I’ve heard, seen and read about where others were not so lucky, some having the possibility of reducing their injury if that had just gone to the doctor.

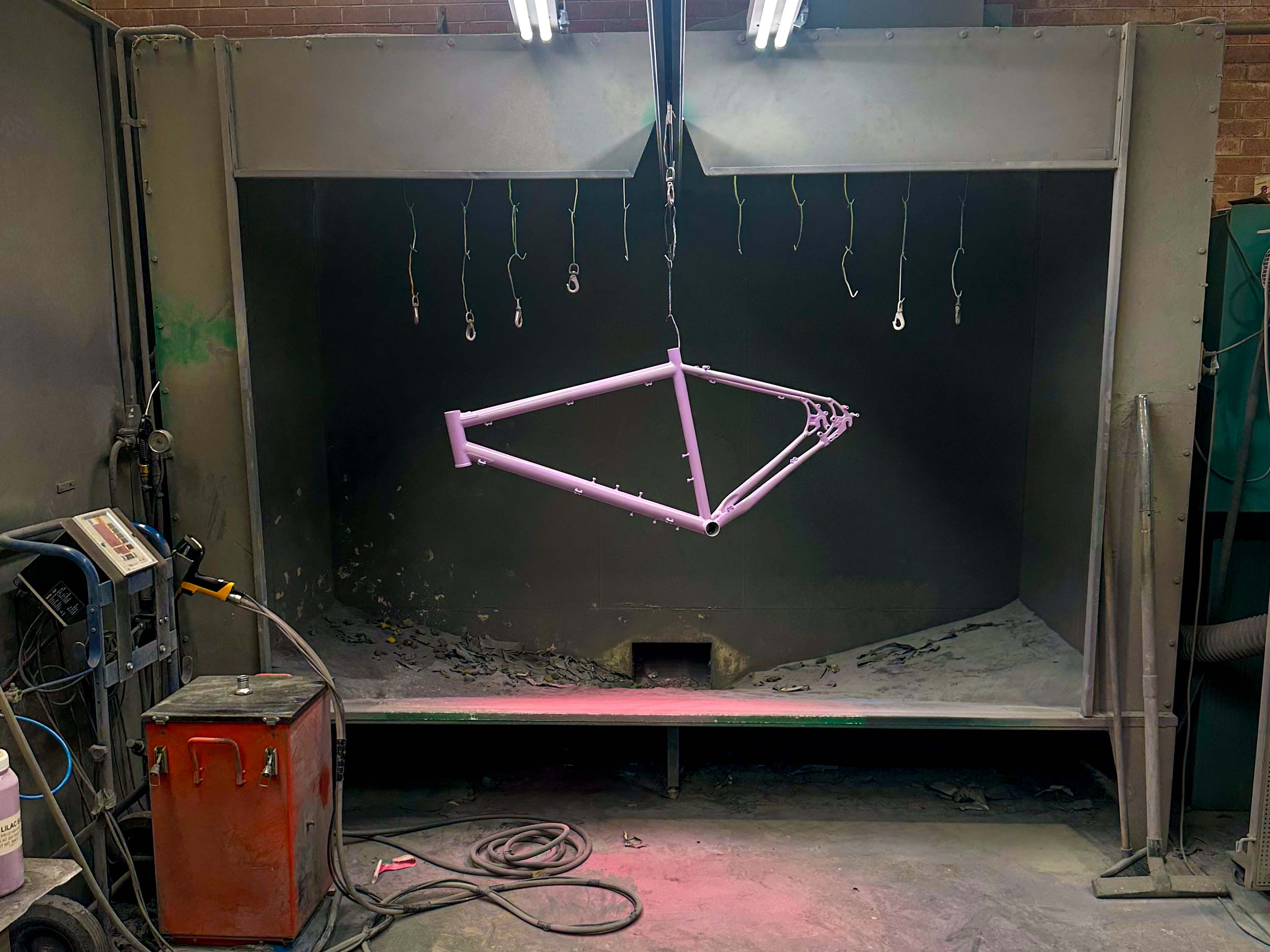

Bikes by Steve | Custom Bicycle Paint

Tour De Melburn | Early Bird Registration